Unlike Montana’s Plains Indians, who migrated west from the northeastern corner of the continent and ultimately settled in present-day Montana, the Bitterroot Salish history begins and ends in the same place.

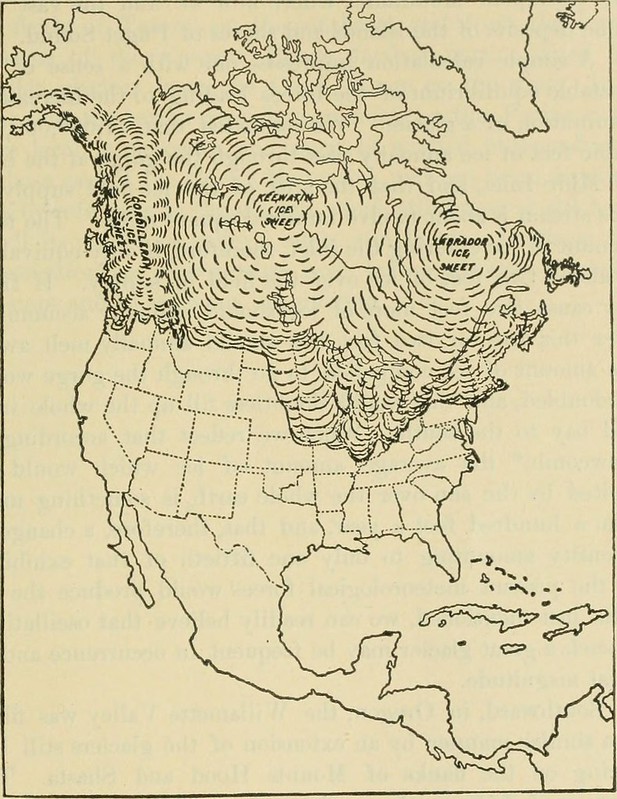

The rich, forested plateau of America and Canada’s Pacific Northwest has been their home since day one, with their Oral history aligning with events that took place in this region over 40,000 years ago, during the last ice age.

Today, this territory is a lush, green, mountainous region that captivates all who visit. While the history of the Bitterroot Salish involves more fish than bison and more huts than teepees, the tribe lived an interesting life incorporating the lifestyles of both the Plains and Plateau Indians.

Read on for a complete history of the fascinating and profound Bitterroot Salish tribe of Montana.

Video summary of this blog (2:07)

Visit us on YouTube for more content on Montana.

History of the Salish Tribe [CONDENSED]

Table of contents:

- Quick facts about the Salish

- Ancient origins of the Salish

- Where the terms “Salish” and “Flathead” came from

- First records of the Salish in modern history

- Way of life

- Neighboring tribes and bands

- Acquisition of horses, around 1700

- Driven west off the plains into western Montana

- Pushed into the Bitterroot Valley, 1700 – 1750

- Fur trade and the arrival of Jesuits, early 1800s

- Treaty of Hellgate, 1855

- Garfield Treaty, 1872

- Relocation to the Flathead Indian Reservation, 1891

Quick facts about the Salish

Where did the Salish come from?

The Salish tribe originated in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Their territory stretched from the Cascade Range on the Pacific Coast to the Rocky Mountains of Montana. The tribe’s oral histories align with events taking place in the region 40,000 years ago, during the last ice age.

How old is the Salish tribe?

Oral histories from the Salish tribe place their origins in America and Canada’s Pacific Northwest over 40,000 years ago, during the last ice age.

What did the Salish tribe speak?

The Salish tribe spoke a language generally referred to in modern times as Salish, which means “of the people”. Before the colonization of North America, over 100 tribes living throughout the Pacific Northwest of Canada and America spoke various dialects of the Salish language.

What did the Salish tribe do?

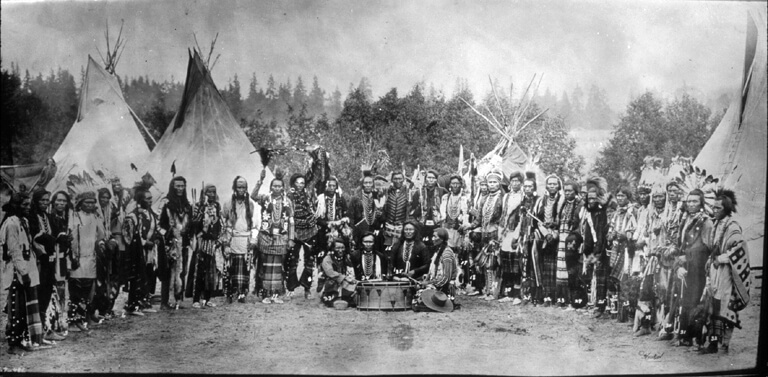

The lifestyles of different Salish bands differed greatly. The coastal Salish tribes were known for weaving and totem pole construction. Eastern Salish bands, including the Bitterroot Salish, hunted bison and lived in teepees like the Plains Indians.

Like all Native American tribes of the time, the Salish lived off the land and relied on animals, such as deer, elk, and bison, and natural resources, such as trees, grass, plants, roots, and berries, for much of their lifestyle.

What does the name Salish mean?

The term Salish is an anglicization of the term Séliš, which means “of the people”.

Do Salish people still exist?

Salish people still exist across the northwestern United States and western Canada. Some Salish tribe members live on Indian reservations in both countries.

Salish Indian Reservations include the Flathead Indian Reservation in northwest Montana and the Coleville Reservation in Washington state.

Is Salish a First Nations?

The Salish are a First Nations tribe whose historical lands spanned across America and Canada’s Pacific Northwest. Ethnicities within the Salish tribe include the Coastal Salish, North Straits Salish, and the Staulo (Fraser River Indians).

Ancient origins of the Salish

The Bitterroot Salish tribe was originally a large, powerful division of the much larger Salish tribe, whose ancient territories spanned across the American and Canadian Pacific Northwest, from the Cascade Range along the Pacific coast to the Rocky Mountains of present-day Montana.

More than 100 tribes of this region were identified by their use of some form of the Salish language.

Historic records indicate the Salish lived in this region of North America anywhere from 10,000 to 40,000+ years.

Salish oral history

According to the Salish oral history, their people were placed in these indigenous homelands near present-day Montana when Coyote killed the “nałisqelixw”, or people-eaters.

First, the creator put animal people on earth, which posed a threat to man. So Coyote, with his brother Fox, arrived to kill off the evils. Although they were successful, leaving man with skills and knowledge, Coyote also left behind many of the vices we still face today, such as greed and envy.

Coyote and Fox created many of the prominent geological features of the region. These oral stories include many events that coincide with modern historian’s understanding of what happened on this land since the last ice age.

The Coyote stories describe the extension of glaciers to Flathead Lake, the flooding of western Montana (Glacial Lake Missoula), the final retreat of the cold weather and ending of the ice age, and the disappearance of large animals, such as the giant beaver, which were replaced by smaller versions.

According to archaeologists, the Salish likely occupied this region of the continent starting roughly 12,600 years ago, during the final retreat of the glaciers. However, stories from the tribe’s oral history align with events that took place 40,000 years ago, when the ice age had already started.

Where the terms “Salish” and “Flathead” came from

“Salish”, which means “the people”, is an anglicization of Séliš, which modern historians and anthropologists use to describe the geographically contiguous block of tribes across the Pacific Northwest who speak a similar language.

However, the term also refers to the Bitterroot Salish, a band that lives on the Flathead Indian Reservation in northwest Montana.

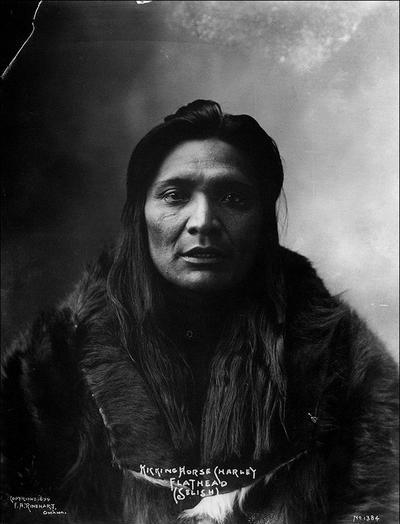

The first modern records of interaction with the Bitterroot Salish come from trapper Andrew Garcia, explorer David Thompson, and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which passed through Bitterroot Salish territory in 1806.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition called the Bitterroot Salish tribe the “Flathead”. Some believe that the term originates from the practice of skull binding, which changes the shape of the skull. However, historians argue that the Salish never practiced skull binding.

In fact, the Bitterroot Salish claim that the term “Flathead” originated from their sign language. The tribe identified themselves by pressing their hands along either side of their face, which meant “we, the people”.

First records of the Salish in modern history

The Salish were the first tribe to have diplomatic relations with the United States. As a result, the federal government used the term Salish to refer to all people speaking a related language.

One of the inland groups of Salish that came to reside around Flathead Lake, Flathead Valley, and the Bitterroot Valley are now called the Bitterroot Salish.

Compared to many other Salish tribes, the Bitterroot Salish were located farther east, occupying much of western Montana, including the Flathead Lake, Flathead Valley, and the Bitterroot Valley.

Their geographical location greatly impacted their way of life, which differed greatly from the coastal Salish, who were far from the bison herds, relied primarily on fishing and agriculture, and were known for their iconic totem poles.

The eastern Salish tribes’ original territory stretched from British Columbia through Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, comprising roughly 22 million acres (89,000 km2) up until they were forced onto reservations around the end of the 19th century.

Way of life

The Salish, including the Bitterroot Salish, were considered Plateau Indians because of the plateau on which they lived, which stretches across this region of the continent.

It is a semiarid region, consisting of sagebrush, grass, and scattered pine groves cut through by many rivers and streams. They had regular access to plentiful salmon and fish, which served as an unusually reliable food supply for native tribes.

Most Salish tribes were autonomous, loosely organized bands of related families, each with a chief and local territory. In winter, they would set up camp in a river village, while in the summer they would travel, camp, fish, and gather berries, plants, and roots.

While the tribes in the central region of the Salish territory, such as Sanpoil, did not embrace complex social and political organizations, and generally didn’t participate in warfare or external trade, the tribes on the fringes were different.

The Bitterroot Salish, who lived in the east, were horsemen, bison hunters, and warriors with a well-developed system of social and political organization, including tribal chiefs and councils, like the Plains Indians.

While the coastal Salish had plentiful access to fish in the streams of the Pacific Northwest, the Bitterroot Salish had some of the same lifestyle practices of the Great Plains tribes, such as hunting bison and living in teepees.

Like the Plains tribes, the Bitterroot Salish relied on bison meat for sustenance and fashioned household items, clothing, and tools from other parts of the animal. They would use natural dyes to color their clothing and were known for decorating various items with porcupine quills.

The Bitterroot Salish also hunted deer and elk, and during the spring and summer months, they gathered various plants, roots, and berries, particularly camas root and chokecherries. They would dry the meat they hunted and make various, preservable dishes which they would store to last them through the winter.

Salish weaving

While the artistry of different bands of Salish, from the coast to the interior areas around present-day Montana differed, many of their artistic practices held similarities.

The coastal Salish were weavers, using plant and animal fibers, including goat wool, down, cedar bark, milkweed, hemp, and nettle fiber.

A primary animal fiber they used came from their flocks of woolly dogs, which they kept and bred for their wool.

The tribe would shear the dogs, spin the wool into yarn, and sometimes combine materials from different sources. They would weave rugs and other items with beautifully intricate designs, including their iconic zig-zags, squares, diamonds, Vs, and chevrons.

However, when the Hudson’s Bay fur trade finally reached Montana and the Pacific Northwest by the early 1800s, it brought with it cheaper, machine-made blankets and rugs, causing a significant decline in demand for handmade items.

The Salish shifted to sourcing yarn from fur traders, as it proved to be more cost-effective than keeping herds of woolly dogs.

Other common practices of the coastal Salish bands include using the enormous Western Red Cedar trees to create homes, household items, such as mats and baskets, as well as clothing. Coastal Salish were known for their totem pole construction. However, the Bitterroot Salish didn’t adopt this practice.

Ceremonies

Unlike the Plains Indians, whose sacred annual ceremonies included the Sun Dance, which they celebrated in the summer, one of the most central ceremonies to Salish culture was the Spirit Dance, a winter ceremony that involved feasting and prayers in honor of guardian spirits.

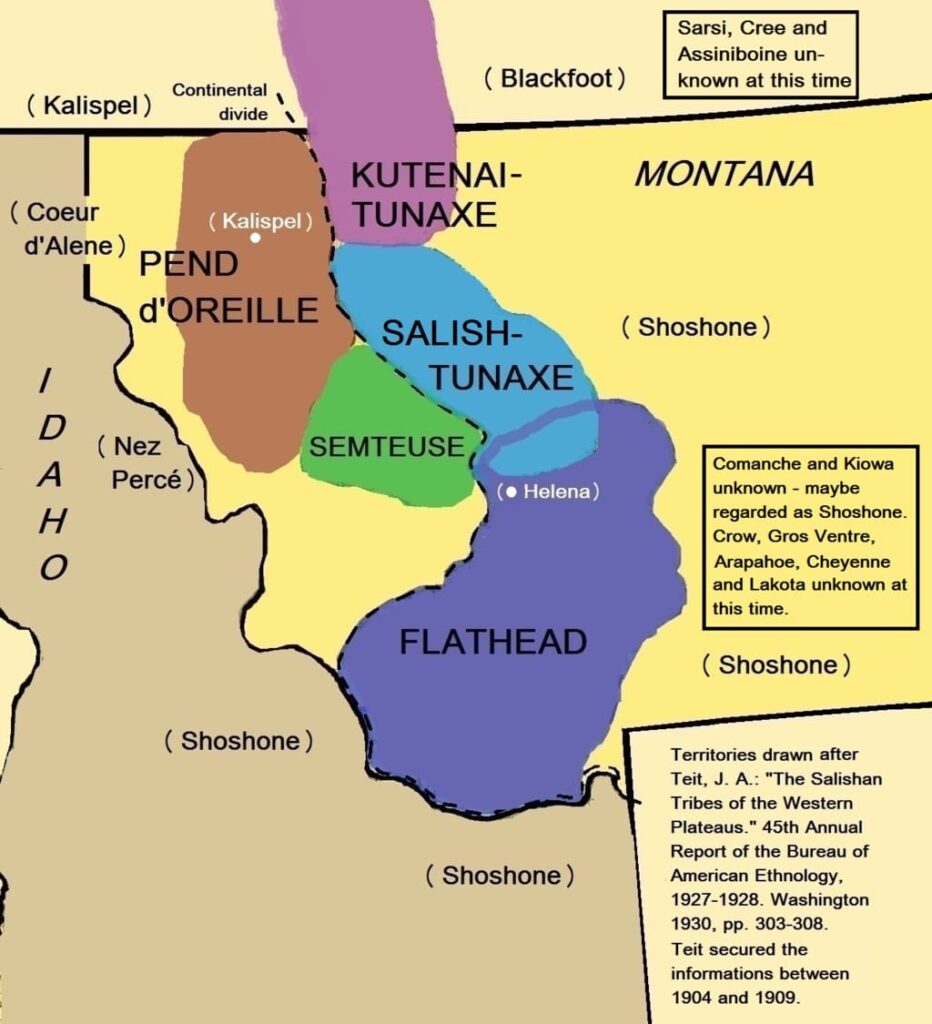

Neighboring tribes and bands

As mentioned previously, the Bitterroot Salish lived mostly around the Bitterroot Valley.

They were surrounded by various neighboring tribes, with whom they mostly had friendly relations. For example, the Salis-Tunaxe lay immediately to the north. With no definite border, tribe members of both bands often intermarried.

Other neighbors included the Kutenai-Tunaxe further north, the Pend d’Oreilles to the northwest near present-day Flathead Lake, and the Semteuse to the south.

Further southwest, west, and east lay other tribes, such as the Sarsi, Cree, Assiniboine Tribe, Crow, Arapaho, and Cheyenne. Historic records indicate that the Bitterroot Salish had very contact with them.

However, the Salish’s primary enemy, the Blackfeet, lay just east, often cutting the Salish off from bison territory on the plains.

Acquisition of horses in the 1700s

Like other Native Tribes across North America at the time, when the Bitterroot Salish acquired horses in the 1700s, it dramatically changed their way of life.

Before, the tribe hunted bison, elk, and horses equally. The acquisition of horses gave them unprecedented speed and strength for travel, hunting, and warfare, and like the Plains Indians, they soon shifted away from elk and deer, giving greater focus to bison hunts.

This drastic change in lifestyle influenced all areas of their lives, including the structures in which they lived. They soon shifted away from living in conical tents constructed from sewn tule mats and started constructing teepees.

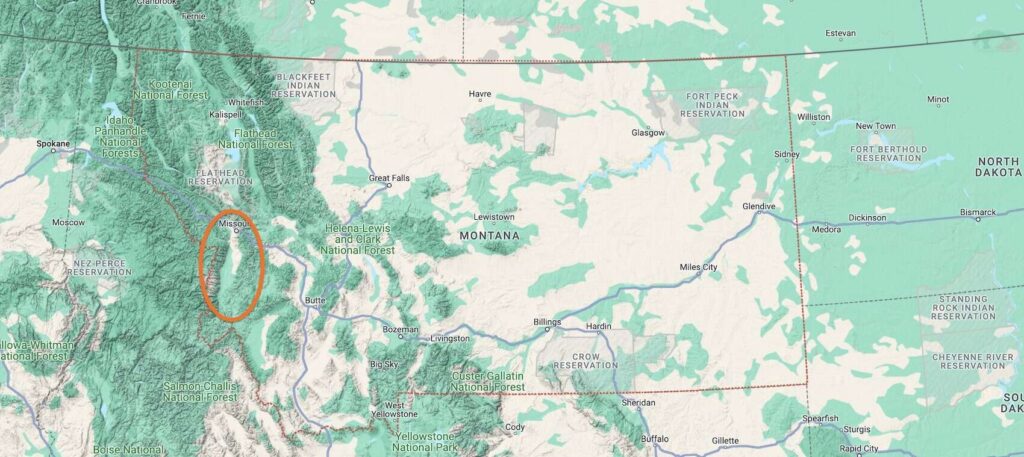

Driven west off the plains into western Montana

Bitterroot Salish originally lived entirely east of the Continental Divide, in present-day Broadwater, Deer Lodge, Madison, and Gallatin counties.

Originally, the Bitterroot Salish had headquarters near the east slope of the Rocky Mountains. Their winter quarters were around Helena, Butte, east of Butte, and in the Big Hole Valley.

The easternmost edge of their hunting territory included the Gallatin Range, Crazy Mountain, and Little Belt Ranges.

Occasionally, the tribe also hunted west of the Continental Divide but rarely ventured west of the Bitterroot Range.

However, the Blackfeet often encroached on Salish lands, pushing them further and further west.

Pushed into the Bitterroot Valley, 1700 – 1750

As Plains tribes continued to expand westward throughout the 18th century, the Bitterroot Salish were forced to move further westward themselves, off the plains.

The Bitterroot Salish also faced a serious smallpox outbreak around this time, which passed on to the tribe from the increasing influx of European settlers.

Adapting to their new circumstances, the Bitterroot Salish sought alliances with tribes further west to strengthen their defenses against their primary enemy, the Blackfeet. They only returned to the plains a handful of times each year to hunt bison.

As other bands of the region, such as the Salish-Tunaxe, faced increasing threats from the encroaching Blackfeet and were further decimated by smallpox, they also formed alliances with the Bitterroot Salish, expanding their shared hunting grounds.

A final push from the Blackfeet forced the Bitterroot Salish across the continental divide to the area around the present-day Bitterroot and Flathead Valleys, where they established a new territory.

It wasn’t long before the Bitterroot Salish would face further transformations to their lifestyle, with the arrival of the fur trade and later the Jesuits.

Fur trade and the arrival of Jesuits, early 1800s

After Lewis and Clark passed through Bitterroot Salish territory in 1806, later came the fur trappers, who hunted a large number of animals, nearly decimating entire animal populations. While this largely impacted the Bitterroot Salish way of life, it was only the beginning.

Before Lewis and Clark made their way through Bitterroot Salish territory in 1806, a Salish prophet named Shining Shirt had a vision foretelling of black-robed men bearing crosses coming to their land to teach them a new set of morals and a new way to pray.

While these men would bring peace, their arrival would also change the tribe’s way of life.

Between 1815 and 1820, Jesuit-educated Iriqouois visited the Bitterroot Salish and spoke of the black-robed men who had been teaching them the powerful religion of Catholicism for hundreds of years.

Remembering Shining Shirt’s vision, the Salish sent multiple delegations to St Louis over the following decade requesting Jesuits visit them to impart their teachings to the tribe.

In 1839, Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet, S.J., agreed to visit Salish territory, and by 1841, multiple Salish, including leaders Tjolzhitsay (Big Face), Walking Bear, and Victor (Many Horses), had been baptized and adopted Catholicism.

On September 24, 1841, St Mary’s Mission was founded – the first permanent non-indigenous settlement to be established in Montana.

Many of the Catholic customs were harmonious with Salish beliefs and practices, such as the ideas of generosity, obedience, community, and respect for family. They also embraced Catholic chants, prayers, hymns, the idea of water as purification, and so on. However, the Salish rejected certain aspects of the religion.

Ultimately, the Jesuits of the time took actions that would push out much of the Salish traditional way of life. They played a major role in the assimilation of the Salish into the European way of life.

As a result of forced assimilation, much of the knowledge, practices, and wisdom of tribal medicine men was lost throughout this time. Suppression of Salish culture and tradition both physically and spiritually continued in new and more powerful ways throughout the rest of the 19th century.

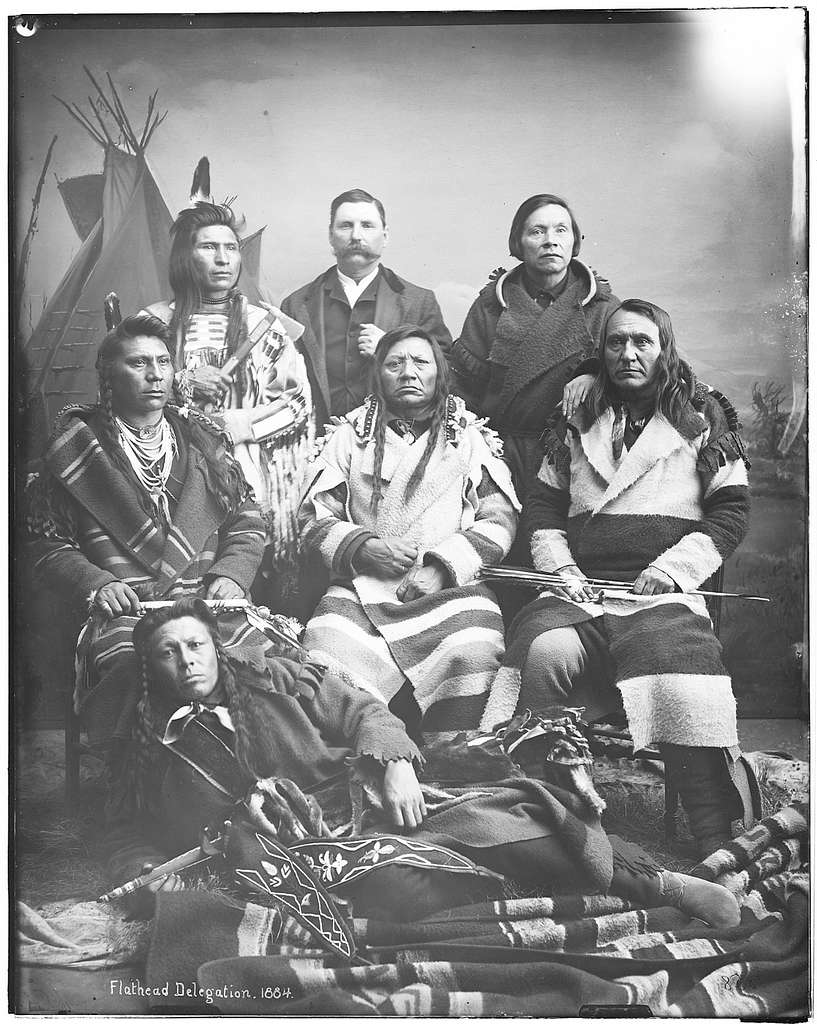

Treaty of Hellgate, 1855 (The long fight for the Bitterroot Valley)

In 1855, Isaac Stevens, the Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Washington Territory invited Bitterroot Salish Chief Victor, Pend d’Oreilles Chief No Horses, and Kootenai Chief Michelle to discuss a peace treaty in present-day Missoula.

This treaty would later become known as the Hellgate Treaty of 1855. The tribal chiefs came with the understanding they would be formally ratifying an already developing friendship with the United States and establishing a lasting peace.

However, non-native populations had become drawn to the Bitterroot Valley for its agricultural value and temperate winter climate. Stevens’ intentions were to cede the Bitterroot Valley from the tribes.

Upon their arrival, the chiefs were surprised to learn of Stevens’ intentions. Moreover, the entire negotiations were marred with miscommunication and misunderstanding. The official translator who was hired for the negotiation process struggled to grasp the Salish language.

In the midst of these cumbersome negotiations, Stevens tried to persuade the tribal chiefs to cede the Bitterroot territory by offering them $120,000 for it. Stevens’ goal with the Salish at the time was the same as his goal with many other Plateau Indian tribes – to move multiple groups onto a single reservation.

His proposal would also establish the Flathead Indian Reservation, which constituted merely a fraction of the tribe’s entire territorial holdings. Under the treaty, the tribes were to cede their land and be moved to the reservation.

Bitterroot Salish Chief Victor refused to give up their land in the Bitterroot Valley. In a sly, and underhanded move, Stevens then decided to insert Article 11 into the agreement.

Article 11 stated that an area of about 1.7 million acres around the Bitterroot Valley would be designated as a provisional reservation.

The United States would then conduct surveys of the Bitterroot Valley and the Flathead Valley and later “determine” which region would better suit the needs and wants of the tribe, with the tribe later being moved onto the newly created reservation.

Until a decision was made, the federal government was to prevent European settlers from encroaching on this territory.

Due to inadequate translations, Article 11 was poorly understood by the Salish. Not fully understanding the details of the treaty, Victor signed it, thinking his tribe wouldn’t be forced to cede the Bitterroot Valley and would remain on their land.

Congress failed to ratify the treaty in 1859, leaving it in limbo over the following several years.

Meanwhile, Stevens ordered a survey of the land. Sending R.H. Landsdale to ride across both reservations, Stevens nudged Landsdale to choose the Flathead Valley for the tribe by telling him that the tribes preferred the Flathead Valley.

Upon his return, Lansdale followed Stevens’ orders and reported that the Flathead Valley was more suited to the needs and wants of the Bitterroot Salish tribe.

However, further delays back east postponed the formal establishment of the Flathead Indian reservation. Victor and his tribe remained on their land in the Bitterroot Valley over the next 14 years, continuing to believe they would be allowed to live there forever.

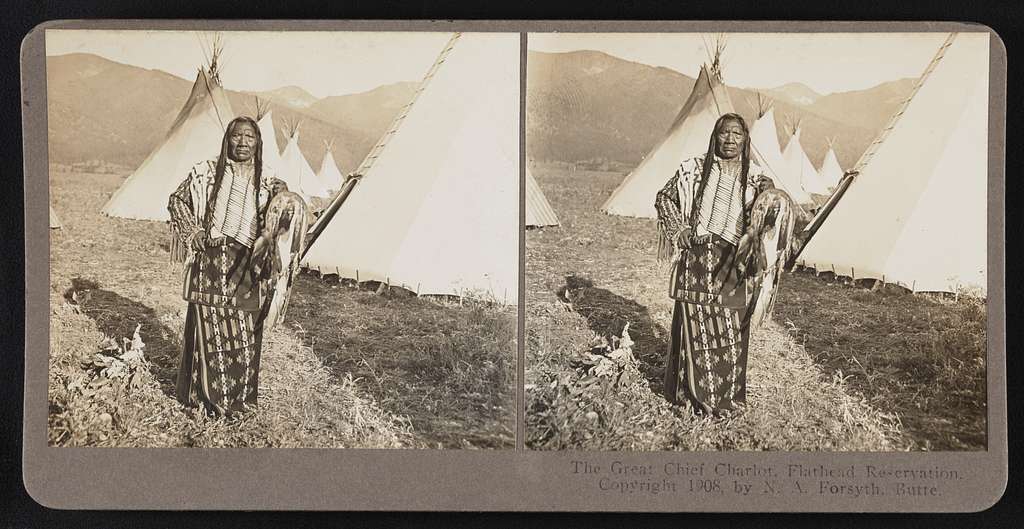

Garfield Treaty, 1872, a second attempt at removing the Bitterroot Salish

In 1870, Chief Victor passed away, ceding his chiefhood to his son Charlot (Claw of the Little Grizzly). Like his father, Charlot maintained a policy of nonviolent resistance to the settlers. Charlot also insisted on his people’s right to remain in the Bitterroot Valley.

When the 1864 gold rush kicked off in Montana, a large influx of settlers and miners arrived in Montana, and government officials started putting more pressure on the Bitterroot Salish to cede their lands in southwestern Montana.

Thinking they could persuade Charlot into ceding the Bitterroot Valley to the United States, in 1871 lobbyists began pressing President Ulysses S. Grant to finalize the surveys and push the tribe north to the Flathead Valley.

That same year, James Garfield traveled on an executive order to meet Charlot and force them from the Bitterroot Valley north to the newly established Flathead Indian Reservation.

Charlot ignored their demands and threats of war and refused to sign the agreement. Nonetheless, officials forged Charlot’s “X” and sent it to the Senate for ratification, enraging the tribe and strengthening their resolve to remain on their land.

To secure a formal signature on the agreement, government officials deemed a second individual as chief, who signed the agreement and led a small group of tribesmen north to the Flathead Indian Reservation in 1873.

However, most of the tribe stayed in the Bitterroot with Charlo, many of whom received rights to farm in the valley. While they saw themselves as an independent tribal community, the federal government deemed them as citizens who had severed ties with the tribe.

Relocation to the Flathead Indian Reservation, 1891

Eventually, the Salish, Pend d’Oreilles, and Kootenai tribes came to a clear understanding of the initial intentions behind the Hellgate Treaty.

Under the terms of the treaty, the tribe ceded over 20 million acres (81,000 km2) of land to the federal government, retaining only 1.3 million acres (5,300 km2) to themselves, which formed the Flathead Indian Reservation.

Throughout the late 1880s, conditions in the Bitterroot Valley grew almost untenable. The tribe continued to hunt and gather throughout the region for as long as they could, but the dwindling bison populations forced them to turn to agriculture.

While they found some minor success with agriculture, a brutal drought in 1889 halted their productivity. Meanwhile, the Missoula and Bitter Root Valley Railroad was built through the tribe’s lands without permission or payment.

With food scarce and facing increasing suffering, the Bitterroot Salish started considering the U.S. government’s offer to live on the Flathead Reservation.

The march northward

In October of 1889, retired general Henry B. Carrington traveled to the Bitterroot with the goal of negotiating with Charlot and the tribe and convincing them to finally move north.

To gain Charlot’s trust, Carrington brought him gifts and grand promises. Families would be able to select farms of their choice on the reservation and each would receive a cow. They would also get help plowing and fencing their land and have government-supplied rations until they received money from the sale of their land in the Bitterroot Valley.

At first, Charlot rejected the offer and asked for the terms set out in the original stages of the Hellgate Treaty, which allowed the tribe to remain in the Bitterroot Valley. Carrington refused.

On November 3, 1889, realizing they needed to comply with the government’s demands to preserve their culture, Charlot signed the document and agreed to leave the Bitterroot Valley.

Congress delayed proceedings for another two years while the tribe faced increasing levels of starvation and suffering.

On October 15, 1891, the Salish finally departed from their historic territory in the Bitterroot Valley and marched a brutal 60 miles (96 km) north to the Flathead Indian Reservation.

At first, Charlot gathered his people and insisted on making the journey on their own, without a government escort.

However, Salish oral history and news accounts from the time reveal that troops from Fort Missoula arrived in the Bitterroot Valley in October of 1891 and forced Charlot and his people off their land, escorting them north to the Flathead Indian Reservation.

The three-day, 60-mile (96-km) journey, has become known as the “Salish Trail of Tears”. Since then, the Bitterroot Salish have lived on the Flathead Indian Reservation with their brotherly Kootenai and Pend d’Oreille tribes.