History of the Crow Tribe

The Crow tribe’s origins can be traced back to the ancestral Hidatsa tribe that lived near Lake Eerie in present-day Ohio.

Facing increasing threats from the newly-armed Iron Confederacy, they were pushed west into present-day Manitoba and later into North Dakota, eventually settling in southeastern Montana.

Upon arriving in the west, the Crow abandoned the sedentary ways of their lifestyle on Lake Eerie, adopting the ways of the Plains Indians, living a nomadic life centered around the game they hunted and berries, plants, and roots they gathered.

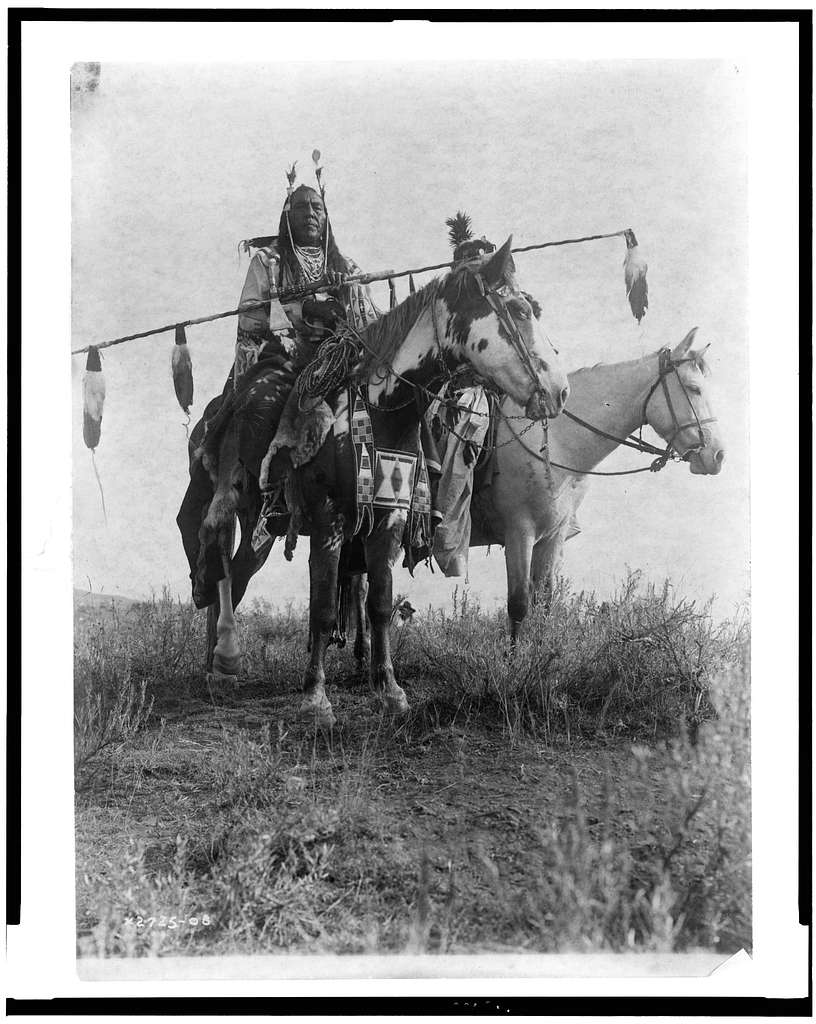

As horses became increasingly valuable to the Plains’ way of life, for hunting bison and transporting their belongings, the Crow became especially known for relatively large horse herds, which they adorned with elaborate regalia.

By allying with the U.S. Army in the late 19th century, the Crow emerged through the Indian wars with a relatively larger reservation than other tribes of the country. However, whether that constitutes fair compensation remains a question.

Read on for a full, condensed history of the Crow tribe.

Complete history of the Crow Tribe [CONDENSED]

Table of contents:

- Lake Eerie Origins

- A Vision

- Migration to present-day Montana

- Split into four bands

- New, historic territory

- Adopting the Plains lifestyle

- Influx of settlers

- Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851

- Plenty Coups’ vision

- Increased warfare

- Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868

- Defeating the Lakota and Cheyenne

- Establishing the Crow Reservation in southeast Montana

Lake Eerie Origins

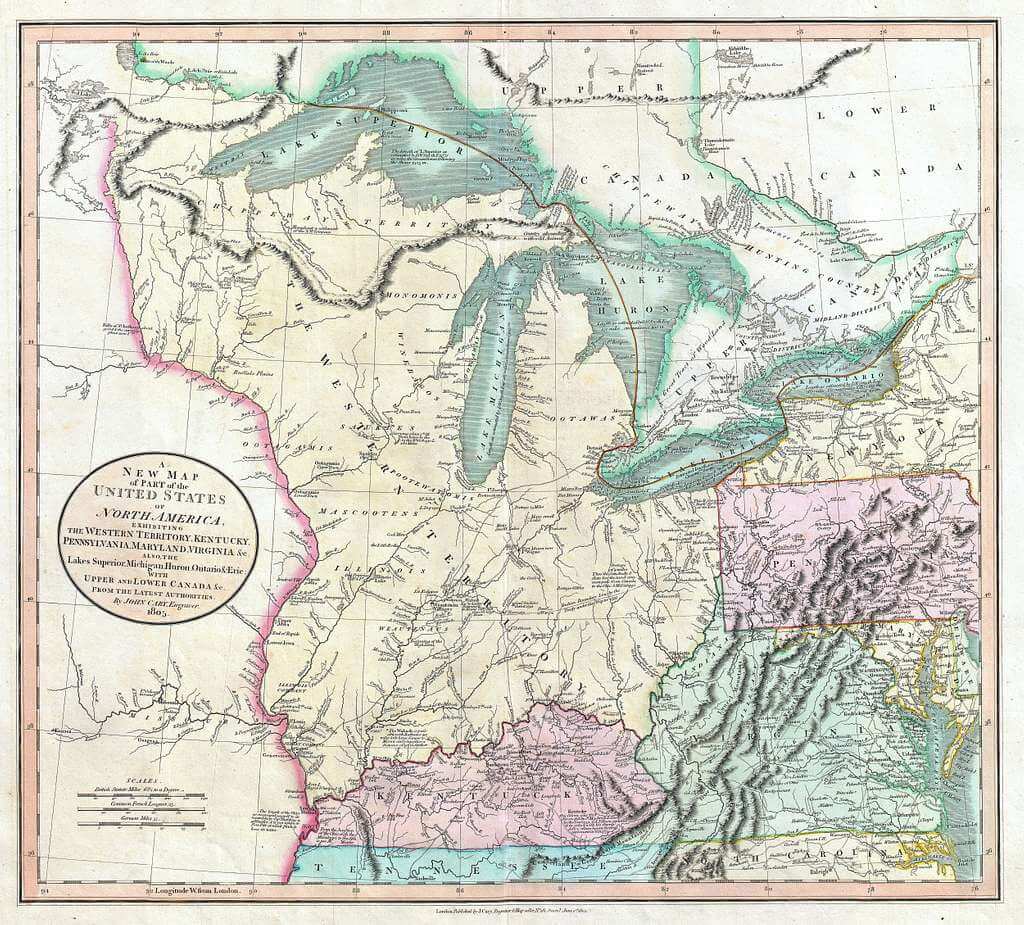

The earliest records of the Crow tribe date back to the 1600s, when they lived a sedentary, agriculture-based lifestyle near Lake Eerie in present-day Ohio.

In the 1600s, The Iron Confederacy, which consisted of various tribes, including the Salteaux and Cree, had greatly benefited from the fur trade, acquiring modern guns, posing a major threat to nearby tribes.

Facing this new threat, the Crow migrated west to a region south of Lake Winnipeg in present-day Manitoba. Continuing on, they eventually settled near Devil’s Lake in present-day North Dakota.

It was here that the tribe split in two, with one band migrating towards southeast Montana while the other remained.

A vision

The Crow Tribe that had settled at Devil’s Lake consisted of two bands, one led by Chief No Intestines and another by Chief Red Scout.

Seeking spiritual guidance as they migrated west, No Intestines received a vision of sacred tobacco seeds and was instructed to travel west to find them in the region of present-day southeastern Montana.

Red Scout’s vision produced an ear of corn, instructing him to remain at Devil’s Lake and plant the seeds for sustenance.

Migration to present-day Montana

Upon arriving in southeastern Montana, the Crow tribe began establishing their historic lands in this area, warring with various Shoshone bands, pushing them further west, and allying with local Kiowa and Plains Apache tribes.

When the Kiowa and Plains Apache later migrated south, the Crow remained. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, during the fur trade, the Crow continued to establish their territory around present-day southeast Montana.

Split into four bands

Over time, the Crow tribe split into four separate bands:

- Ashalaho (Mountain Crow). This was the original band of No Intestines’, which lived in the foothills of the upper Yellowstone River, among the Absaroka Range and Big Horn Mountains along the Wyoming-Montana border, and reaching to the Black Hills.

- Eelalapito (Kicked in the bellies). This band lived in the Bighorn Basin, from the area around the Bighorn Mountains and the Absaroka Range south to the Wind River Range in northern Wyoming.

- Binneessiippeele (River Crow). The River Crow occupied the territory along the Yellowstone and Mussellshell Rivers, south of the Missouri River in an area that was historically known as the Powder River Country (Big Horn Valley, Powder River Valley, and Wind River Valley). It is said that the River Crow split from the Hidatsa over a bison meat dispute.

- Bilapiluutche (Beaver dries its fur). According to oral history, there was at one time a fourth Crow band that merged with the Kiowa in the 1600s.

New, historic territory

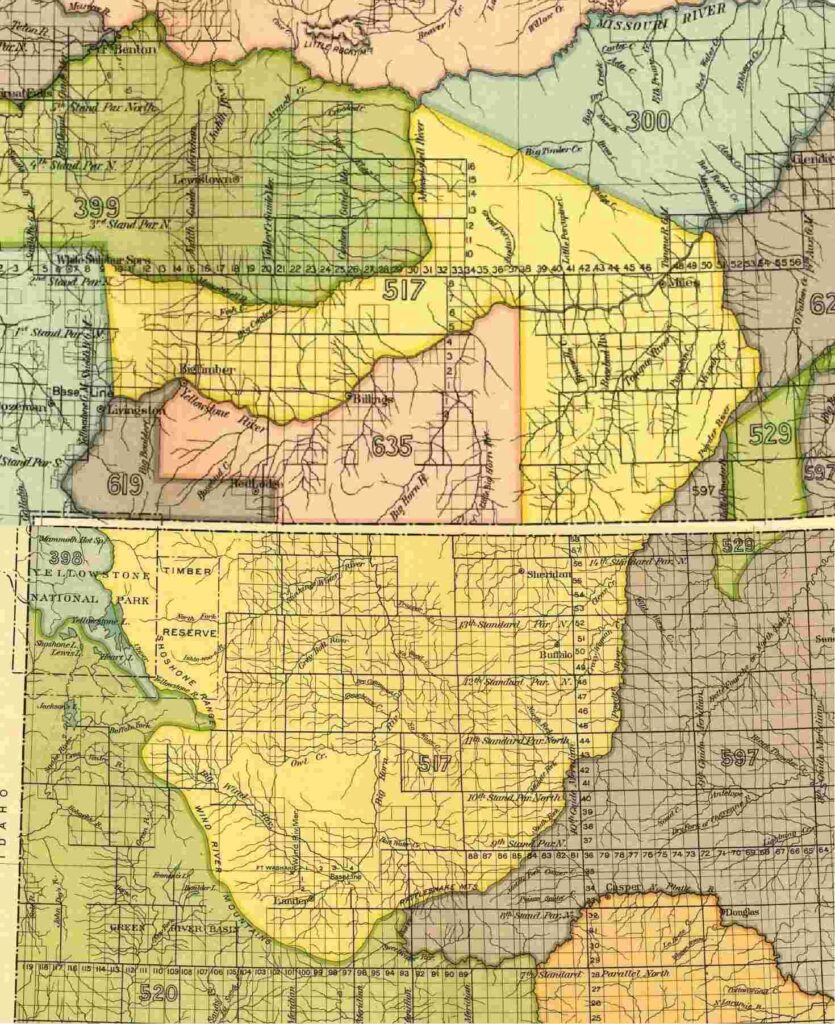

Historic Crow territory spanned across much of southeastern Montana and northern Wyoming, stretching between the following geographical points:

- From the headwaters of the Yellowstone River in the present-day Yellowstone National Park area

- North to the Musselshell River

- Northeast to the mouth of the Yellowstone River at the Missouri River

- Southeast to the confluence of the Yellowstone River and Powder River

- South along the south fork of the Powder River

- Southwest to the Wind River Range

This territory encompassed major regions of southern Montana, including the Powder River Valley, Tongue River Valley, and Bighorn River Valley, as well as the Wolf Mountains, Bighorn Mountains, Pryor Mountains, and the Absaroka Mountains.

To the south, their territory was confined by the Rattlesnake Hills and the Wind River Range of Northern Wyoming.

Adopting the Plains lifestyle

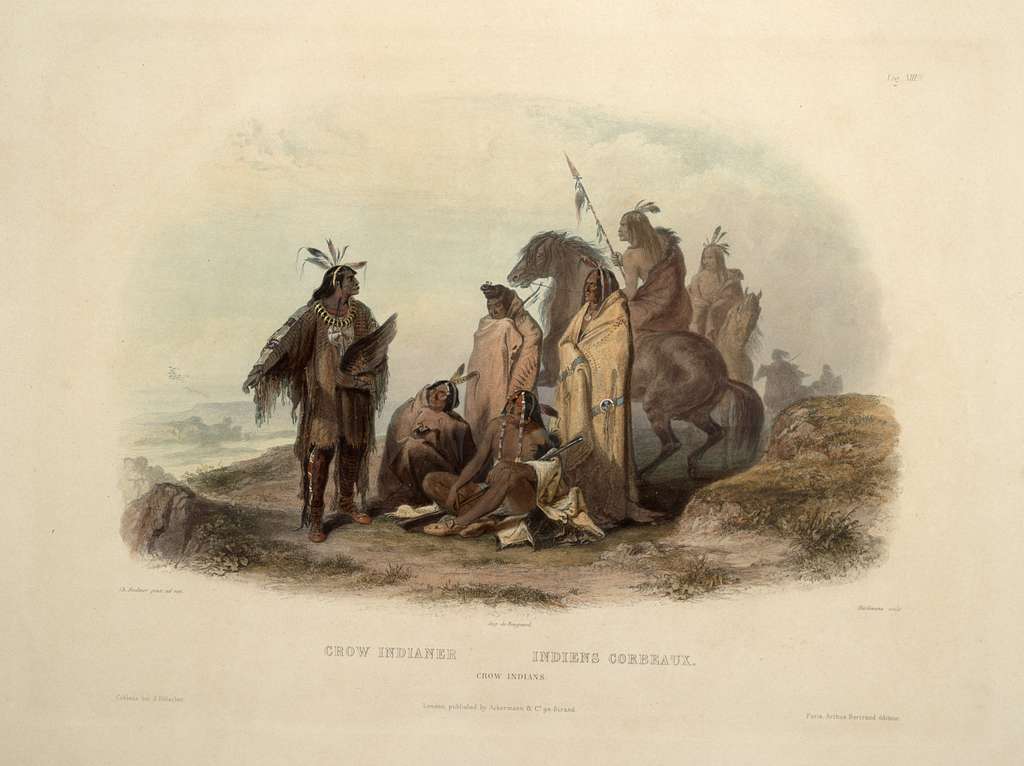

Upon settling in this region, the Crow abandoned the sedentary ways of their life on Lake Eerie, adopting the nomadic lifestyle of the Plains Indians, following the bison herds, and gathering plants, seeds, berries, and roots.

Like many Plains Tribes, their lives centered around the bison, from which they fashioned daily essentials like clothing, shelter, and equipment.

They also practiced many rituals that supported their spiritual beliefs, including the Sun Dance, an annual ceremony of sacrifice and renewal.

The Crow adapted to riding horses, which had quickly become a prized commodity on the plains, for the efficiency they brought to bison hunting and transportation.

Over time, the Crow became known for their relatively large horse herds, which they adorned with beautiful, elaborate regalia.

Influx of settlers

In the 1850s, the transcontinental railroad was merely an idea, with various survey crews spanning out into different regions of the West to determine the best route across the country.

Nonetheless, the only way to travel to California, Washington, or any other western region of the country at this time was by foot, horseback, wagon, or up the Missouri River, which only took you as far as the western regions of present-day Montana.

For decades, people had been traveling west along trails, such as the Oregon Trail and the Santa Fe Trail, which crossed through native territory. As gold was discovered in California and Montana, traffic on these trails and through these territories increased dramatically.

Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851

By the time the European settlers, miners, and fur traders started moving at increasingly faster rates into Crow territory in the mid-1800s, the Crow Tribe had already been facing intense pressure from the neighboring allied Lakota and Cheyenne tribes.

To ease simmering tensions in the region between tribes and between settlers and tribes, the U.S. government established the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851, which set out to achieve the following:

- To allow the U.S. to construct roads and forts on Native territory

- To allow for safe passage on the Oregon Trail (which passed through present-day Wyoming)

- To establish territorial boundaries for native tribes to prevent conflict between the roughly 8 tribes of the region.

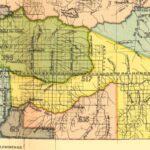

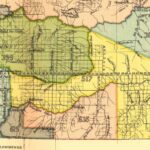

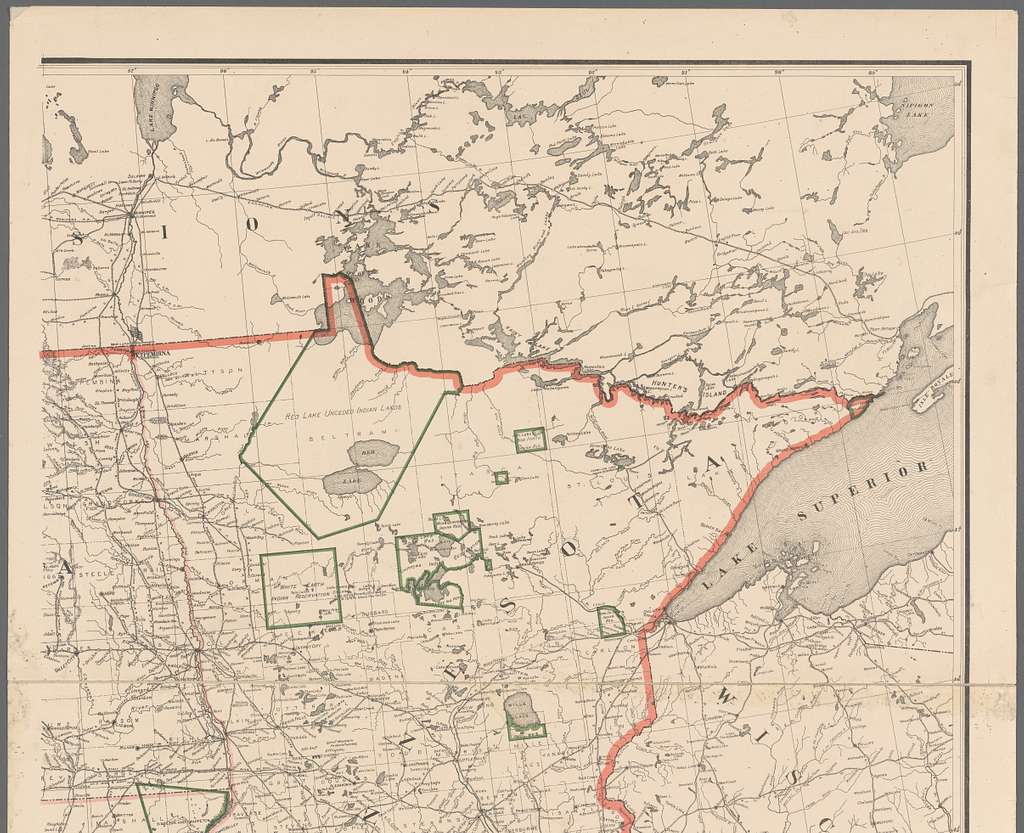

The territorial boundaries of the Crow tribe which were drawn out by this treaty somewhat encompassed the historical regions which the tribe had recently settled, covering southeastern Montana and stretching deep into northern Wyoming to the Wind River Range (see above image).

However, the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1851 fell short in its ability to uphold the newly established tribal boundaries in the long term.

A return to war was imminent, and by 1860, the Lakota and Cheyenne alliance had taken over the Crow’s coveted eastern hunting lands, from the Black Hills of South Dakota to the peaks of the Bighorn Mountains, by sheer right of conquest.

Plenty Coups’ vision

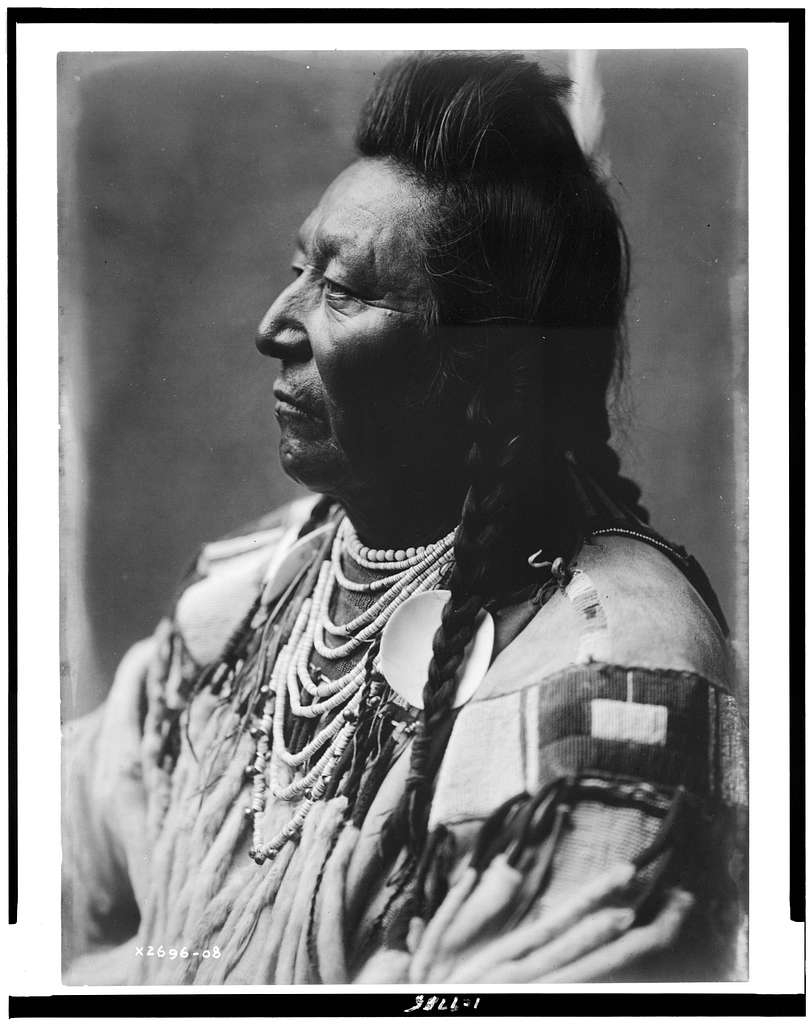

Meanwhile, amid the rising influx of European settlers in the 1850s, a young boy named Plenty Coups, who later became a great Crow Chief, received a vision.

Tribal elders interpreted Plenty Coups’ vision to reveal that the Europeans would soon control the entire country. To retain their land, the Crow needed to remain on good terms with the U.S. A vision the Crow would realize over the following decades.

Increased warfare

As the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie failed to clearly establish and enforce tribal borders, warfare between the Crow and other tribes of the region, as well as warfare between local tribes and the U.S. Army, increased steadily.

Throughout the 1860s, the Lakota and Cheyenne continued pushing west, warring with Crow, stealing their lands, and driving them into the foothills of the Rocky Mountains around the upper Yellowstone River.

Occupying much of the present-day Montana-Wyoming border region, any European intruders now had to face the Lakota and Cheyenne.

Red Cloud’s War raged from 1866 to 1868, driving the U.S. Army off the Bozeman Trail, which connected the Oregon Trail with the booming mining towns of southwest Montana.

After years of tribal warfare, relentless guerilla warfare from the Sioux, Arapaho, and Cheyenne Tribes, rising freight rates, and difficulty finding contractors for the railroads, the U.S. took action again.

Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 stopped the reignited wars around the region of southeast Montana and northern Wyoming, drawing new boundaries for tribal territories.

The treaty officially confirmed Lakota dominance over the region, establishing the Great Sioux Reservation (Lakota were a subgroup of the Sioux) which stretched from the Black Hills of South Dakota across the Powder River Country to the Bighorn Mountains.

The treaty also reduced previously treaty-drawn Crow territory boundaries by roughly 50%.

Defeating the Lakota and Cheyenne

The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 put an end to Red Cloud’s War. However, Indian Wars in the region continued to rage through the 1870s, with numerous Lakota victories, including the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1878.

However, around this time, in 1877, with the help of the allied Crow Tribe, the U.S. Army finally stopped much of the warfare in the region, bringing a near-defeat to the Lakota and their allies.

Many Lakot fled north into Canada, while others were forced onto distant reservations in Montana and Nebraska.

Over the following decades, through various agreements between the Crow and the federal government, the Crow Indian Reservation was established in southeast Montana.

However, the federal government continued ceding areas of the reservation to itself, shrinking the reservation as the decades passed.

Establishing the Crow Reservation in southeast Montana

As previously mentioned, the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 redrew Crow territory boundaries for a second time, ceding the entire region that lay in present-day Wyoming to the federal government while preserving much of what lay in southern Montana.

Over the next several decades, as a result of various decisions, the federal government continued paring down the Crow Reservation, ultimately resulting in the 3,594-mile 2 (9,307-km2) piece of land that constitutes the present-day Crow Indian Reservation in southeast Montana.

The above images show the changing boundaries and shrinking size of the Crow Reservation from 1868 to 1891.

The present-day Crow Tribe Reservation boundaries are similar to the 1891 boundaries, excluding a major section of land that stretched from the current northern boundary north to the southern banks of the Yellowstone River.

Discover the Crow Indian Reservation in Montana

What’s life like on the Crow Indian Reservation today?

One of the biggest events that takes place on the reservation is the Crow Fair, an annual celebration of Crow culture, with dancing, colorful clothing, vendors, food, and more.

Discover life on the Crow Indian Reservation today, including cultural events and key points of interest, in our article, Crow Indian Reservation – Past, present, tourism.

Learn more about the native cultures of Montana

- History of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe [CONDENSED]

- Storied history of the Blackfeet Tribe [CONDENSED]

- History of the Bitterroot Salish Tribe [CONDENSED]

- History of the Pend d’Oreille Tribe [CONDENSED]

- History of the Assiniboine Tribe

- The 11 Native American Tribes that lived in Montana before colonists arrived