The earliest records of the Northern Cheyenne tribe’s history date back to the 17th century, when they were still a part of the Cheyenne Tribe, living near Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes. The Northern Cheyenne lived a sedentary lifestyle, with a fishing and agriculture-based economy.

With increasing pressure from the newly-armed Ojibwa Tribe in the region, the Cheyenne migrated west towards the Dakota territory in the 18th century.

Abanding their sedentary, fishing, and agriculture-based lifestyles of the Great Lakes, they adopted the ways of plains Indians, becoming nomadic hunter-gatherers, living off the animals they hunted and the plants they gathered.

A deeply spiritual tribe, they cherished the land and all living creatures of the earth, holding sacred annual ceremonies, such as the Sun Dance and Renewal of the Sacred Arrows, which renewed the cosmos and empowered tribesmen.

Despite signing treaties with the federal government to establish peaceful coexistence with European settlers in the 19th century, these frameworks deteriorated as gold was discovered in the west and more miners and other settlers flooded into Cheyenne territory.

As the prospects of peaceful coexistence faded, the Cheyenne fought numerous battles with the U.S. army throughout the 19th century. After enduring war, relocation, escape, capture, and escape, the Northern Cheyenne finally settled in southeastern Montana in the 20th century.

Today, the Tribe lives on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation between the Crow Indian Reservation and Tongue River in southeast Montana.

Read on for the condensed history of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Tribe, including where they came from, how they got to Montana, and the events that transpired in between.

History of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe

Table of Contents:

- Great Lakes origins

- Western migration to the Dakota territory

- Split into Northern and Southern bands

- Indian Wars

- Forced south

- Northern Cheyenne Exodus

- Imprisoned at Fort Robinson

- Washington allows them to settle up north

- Establishing the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation

Great Lakes origins

The Northern Cheyenne were originally part of the Cheyenne Tribe, a sedentary, hard-working, fishing, and agriculture-based tribe that lived around Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes region in the 17th century.

Like many plains Indians, their indigenous spirituality played a fundamental role in their way of life. The tribe believed in the Wise One Above and the spirit who lives in the earth.

Of the many sacred ceremonies the tribe participated in were the Sun Dance and the Renewal of the Sacred Arrows.

The Sun Dance was an annual summer ceremony. Among its many rituals, at one point members of the tribe would dance while staring into the sun to enter a trance, gain powers, and ensure the renewal of the cosmos.

The Renewal of the Sacred Arrows was an annual four-day ceremony that took place over the summer solstice, in which only males participated, while women were to remain in their tipis. The ceremony focused on sacred arrows that empowered the tribesmen.

Western migration to the Dakota territory

Facing pressure from migrating tribes in their area around the end of the 18th century, such as the Lakota and the newly-armed Ojibwa, the Cheyenne tribe migrated west, towards present-day North and South Dakota.

By the mid-19th century, the Cheyenne had shifted away from their sedentary, agricultural lifestyle and adopted the typical nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the plains natives.

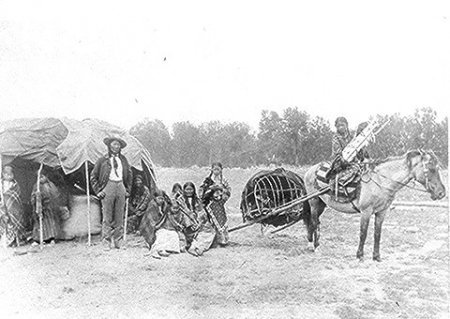

While they used to create homes from the earth, they now lived in tipis. Shifting away from fishing and growing crops, they hunted bison and other animals of their region, including elk and deer, and gathered wild fruits, vegetables, seeds, and roots.

The Cheyenne created many of their daily tools, clothing, and utensils from the animals they hunted, including bags, shelter, mocassins, robes, blankets, and equipment.

They lived cyclically, according to the seasons, using what they hunted and gathered in the summer season to sustain themselves through the winter, when they set up stationary winter camps.

Split into Northern and Southern bands

By 1832, after the Lewis and Clark expedition had passed through this region of the Louisiana Purchase, a portion of the Cheyenne tribe migrated to the area around present-day southern Colorado and northern New Mexico.

A tribal split started emerging, with the southern group forming an alliance with the Southern Arapaho. By 1851, the Fort Laramie Treaty established the first Cheyenne “territory” around present-day Fort Collins, Colorado Springs, and Denver.

When the Gold Rush hit in the late 1850s, European settlers flooded into Cheyenne territory, leading to increased warfare over the following decades, known as the Indian Wars.

Indian Wars

By the 1860s, the Northern Cheyenne largely occupied the Black Hills region, which the U.S. government was actively trying to gain control over.

Resenting the intrusion, the Northern Cheyenne fought many battles with the U.S. Army over the following decades, such as the Sand Creek Massacre (1864), the Battle of Shashita River (1868), and numerous battles of the Black Hills War (1876-1877).

Forced south

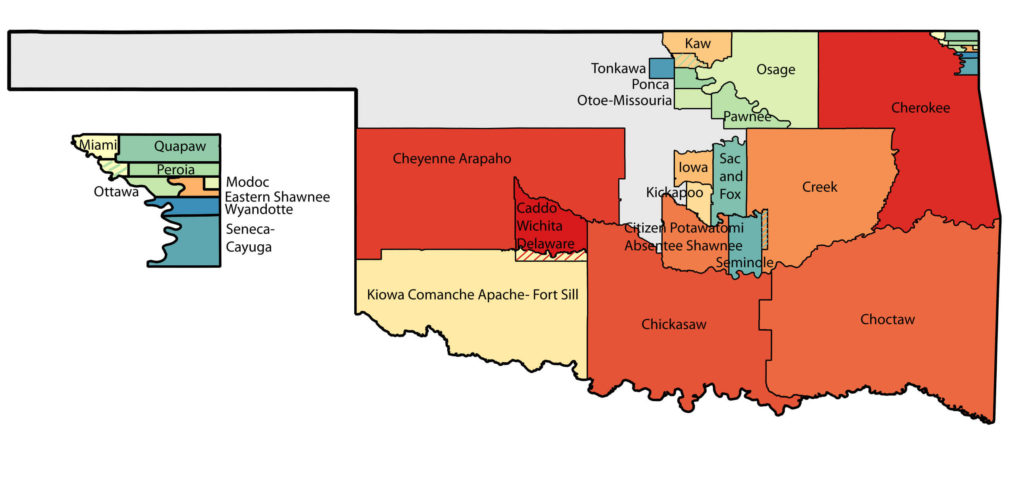

In 1877, the Northern Cheyenne were forced onto the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation on which the Southern Cheyenne lived in Oklahoma.

Many tribe members didn’t survive the journey. Upon their arrival on August 5, their numbers had shrunk from 972 to 937.

They struggled to adjust to the intense southern heat, were forced to abandon their hunting and gathering ways for growing food, and faced brutal conditions in their barracks. The tribe’s numbers continued to shrink.

One early morning in 1878, faced with dismal prospects, one tribal band decided to escape to return north, an event later known as the Northern Cheyenne Exodus.

Northern Cheyenne Exodus

As the band traveled northward through present-day Oklahoma, through the Cimarron Basin, and up towards present-day Nebraska, they effectively outwitted the trailing U.S. Army on multiple occasions.

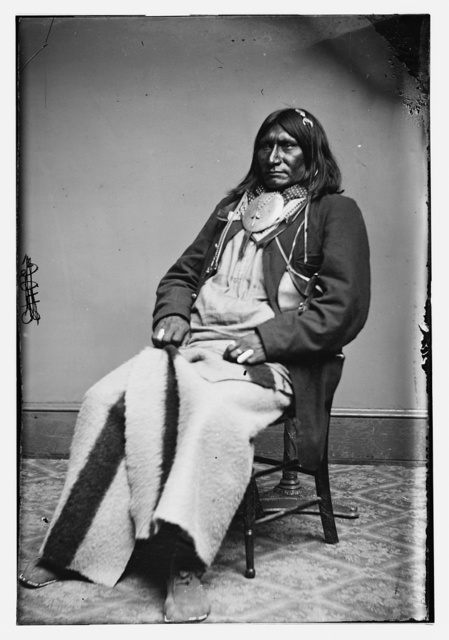

After six weeks of running, the tribal chiefs held council, deciding that they would split into two groups. One band, led by Chief Little Coyote, would continue north to the Powder River country. A second band, led by Chief Morning Star, resolved to stop running and settle in the area of present-day Nebraska and South Dakota.

While en route, Chief Morning Star band suddenly found themselves surrounded by the U.S. Army and agreed to go to nearby Fort Robinson.

Imprisoned at Fort Robinson

Before arriving at Fort Robinson, the tribe dismantled their weapons and guns, the women hiding the larger pieces under their robes and the rest hanging the small pieces as ornaments on their clothing and moccasins.

Upon arrival, Chief Morning Star agreed to stop fighting if the great father Washington would let them settle on Pine Ridge Reservation, where Chief Red Cloud resided with his tribe of over 100,000.

However, on January 3, 1879, Chief Morning Star tribe was instructed to return south. When the tribe refused, the group of 100+ tribe members were locked in a 75-man military barracks without food or wood for heat.

Six days later, after reassembling their dismantled weapons from within the barracks, part of the group attempted an escape.

Roughly 65 were captured by the U.S. Army and brought back. Many other fleeing tribe members perished in the ensuing fights, including Chief Crazy Horse – an event that later became known as the Fort Robinson Massacre.

Washington allows them to settle up north, near present-day Miles City

Shortly after the Fort Robinson Massacre, Washington released Chief Morning Star, his tribe, and other prisoners at Fort Robinson, permitting them to settle in up north in Fort Keogh, near present-day Miles City, Montana.

As for Little Coyote’s band, they generally faced little resistance and conflict on their journey north, eventually settling near the Powder River, not far from Fort Keogh.

Establishing the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation

After settling at Fort Keogh, many families from the Northern Cheyenne Tribe migrated south, establishing homesteads on the Tongue River watershed area of southeastern Montana, a place they considered home.

On November 16, 1884, then-President Chester A. Arthur established the Tongue River Agency for the Northern Cheyenne and other natives in the region, consisting of 371,200 acres (1,502 km2) of land west of the Tongue River. The original reservation didn’t include land further east near the Tongue River where many Northern Cheyenne families had settled.

However, on March 19, 1900, President William McKinley extended the agency’s eastern boundary to the west bank of the Tongue River, increasing its size to 444,157 acres (1,797 km2), encompassing much of the land where many Northern Cheyenne homesteaders had settled.

Sometime after 1939, the reservation was renamed the Northern Cheyenne Agency, later to be renamed the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation.

Discover the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation

Learn about the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, including life on the reservation today and its main points of interest, in our article, Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation.

Learn more about the native culture of Montana

- History of Montana’s Crow Indian Tribe [CONDENSED]

- Storied history of the Blackfeet Tribe [CONDENSED]

- History of the Bitterroot Salish Tribe [CONDENSED]

- History of the Pend d’Oreille Tribe [CONDENSED]

- History of the Assiniboine Tribe

- 11 Native American Tribes that lived in Montana before colonists arrived