Enthusiastic explorers of the West first discovered the region of present-day Glacier National Park in the mid-19th century, then home to native tribes.

The United States government officially declared the region a national park on May 11, 1910. When the Great Northern Railroad reached the park’s southern edge in the 1890s, tourism to the area blossomed.

A major shift occurred when the Going-to-the-Sun Road was completed, forever changing how people experience the park.

Read on for a condensed history of Glacier National Park.

History of Glacier National Park [CONDENSED]

Table of contents:

- Native inhabitants

- 1806 – Lewis & Clark pass by Glacier National Park

- Expeditions into the park (1850s – 1880s)

- First tourists

- Establishing Glacier National Park

- Hill’s Great Northern Railway develops Glacier National Park

- Going-to-the-Sun Road (GttSR) – Forever changing the park experience

- Glacier National Park today

Native inhabitants

Long before European settlers arrived in this region of North America, indigenous tribes called the mountains and alpine lakes of present-day Glacier National Park their home for roughly 10,000 years.

These groups were likely descendants of the tribes we know today as the Flathead, Kootenai, Shoshone, Cheyenne, and Blackfeet.

Before the federal government took over the land containing present-day Glacier National Park, the western slopes of the Livingston and Whitefish Ranges that comprise the western part of the park were home to the Flathead and neighboring tribes.

The eastern slopes of the Lewis Range, which comprise the eastern part of the park, and the rolling hills extending eastward past Chief Mountain mostly belonged to the Blackfeet.

One of the first designated Blackfeet Indian territories was created by the Lame Bull Treaty in 1855. This treaty gave the Blackfeet and their allies, the Gros Ventre, the eastern slopes of the Lewis Range, from the Continental Divide eastward across much of Montana.

But within 40 years, under pressure from local miners to gain access to these lands, Chief Whitecalf ceded a roughly 800,000 ft² (3,200 km²) strip of land along the reservation’s western border to the federal government.

While the agreement gave the tribe usage rights over the land (for hunting), 15 years later, the federal government revoked these rights when they made the same strip of land a part of the newly designated Glacier National Park.

1806 – Lewis & Clark pass by Glacier National Park

In 1806, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition was exploring the Marias River (east of the park), the corps passed within 50 miles (80km) of the park.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition was followed by trappers who were followed by miners who were followed by settlers and homesteaders.

Nonetheless, the area of Glacier National Park remained mostly unexplored until the Great Northern Railway started climbing toward the park’s southern border in the 1800s.

It was during the search for a rail route through this mountainous region of present-day Montana that the first European settlers realized its magnificent beauty.

Expeditions into the park (1850s – 1890s)

When the Great Northern Railway crossed the Continental Divide at Marias Pass (5,213 ft/1,589 m) in 1891, which runs along the present-day park’s southern border, Great Northern Railway president Louis W. Hill realized the splendid beauty that lay just to the north.

The railway established a small depot called Benton near present-day West Glacier.

To generate business for the railroad he started promoting the beauty of the region, branding it as a top tourist destination, encouraging people to travel west on the railroad to explore the region, while simultaneously lobbying Congress to protect the entire area.

“Far away in northwestern Montana, hidden from view by clustering mountain peaks, lies an unmapped corner—the Crown of the Continent.”

George Bird Grinnell (1901)

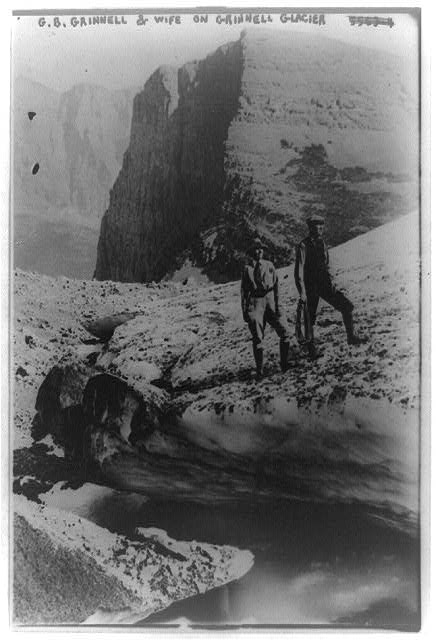

Meanwhile, in 1885, Brooklyn native, anthropologist, naturalist, and writer George Bird Grinnell hired renowned explorer James Willard Schultz to guide him on a hunting trip to the area.

After several later expeditions through this territory, he became so inspired by its beauty that he dedicated the following several decades of his life to protecting it.

Together, Grinnell and Hill would be key figures in the creation of Glacier National Park and its development. Hence, the name, “Grinnell Glacier”.

First tourists

By the late 1890s, tourists had started arriving in the area by train.

A typical trip to Glacier at this time would likely involve a train ride to Belton followed by a stagecoach journey several miles to the southern shore of Lake McDonald. Visitors would then board a boat for an eight-mile journey up Lake McDonald to the Snyder Hotel.

No roads existed in the park, but the large lakes offered a chance for visitors to reach the inner regions of the park.

By 1897, Congress had designated the area a forest preserve. The federal government also granted mining rights to the local miners who were eager to explore the region’s mineral potential, though the mines were largely unsuccessful. Many of the former mine shafts remain in the park today.

Efforts to protect the region continued throughout the early 1900s, with the Boone & Crocket Club, led by Grinnell and Hill, introducing a bill to Congress in 1910 to formally establish Glacier National Park.

Establishing Glacier National Park

The efforts of Grinnell, Hill, and the Boone & Crocket Club eventually proved fruitful. On May 11, 1910, President William Howard Taft signed into law the bill designating the area Glacier National Park.

The official national park designation kicked off a new era of tourism in the region. The park’s first superintendent, William Logan, was appointed three months later, and new staff was hired to manage the park. Staff needed housing and offices, and visitors needed trails, roads, and hotels.

Hill and his Great Northern Railway company wasted no time building the infrastructure that would meet the tourist needs. Today, the results of some of his work are still in full service throughout the park.

Hill’s Great Northern Railway helps develop Glacier National Park

To satisfy the rising demand for infrastructure throughout the park, Hill quickly embarked on the construction of numerous chalets and hotels, connecting each chalet with a network of trails, all of which were financed by the railroad (later reimbursed by the federal government).

The list of chalets Hill built included Belton, Going-to-the-Sun, Two Medicine, St. Mary, Granite Park, Many Glacier, Cut Bank, Sperry, and Gunsight Lake. In 1913, developer John Lewis built the Lewis Glacier Hotel on Lake McDonald, which Hill purchased in 1930, renaming it Lake McDonald Lodge.

Of these, Granite Park, Sperry, and Belton Chalets are still in use, as well as one building of the Two Medicine Chalet (now a concessions facility), the Glacier Park Lodge, Lake McDonald Lodge, and the Many Glacier Hotel. All of them are National Historic Landmarks.

With a vision of promoting the area as America’s Switzerland, Hill modeled the chalets and hotels he constructed throughout the park after Swiss architecture. Hill also created 4 campsites throughout the park.

Throughout the 1910s, a typical journey through the park involved a multi-day horseback journey from chalet to chalet via the park’s trail system, with guests staying at a different chalet each night.

Today, 350 structures throughout the park are on the list of the National Register of Historic Places, including ranger stations, mountain patrol cabins, fire lookouts, and concession buildings.

Going-to-the-Sun Road (GttSR) – Forever changing the park experience

When the park was first established in 1910, the cost of traveling by the Great Northern Railway was beyond many travelers’ budgets, and only a few miles of bumpy wagon trails existed throughout the park.

The idea of creating a road to the park that would then transit through its inner regions was born almost immediately. This would allow for a faster, more affordable means of traveling to the park and visiting its interior regions.

The resulting increased tourism would bring great business to local communities. National Park authorities soon grew a liking for the idea and, after some initial pushback, local businessmen also got on board.

However, cliffs, short dry seasons, 50-foot snow drifts, and walls of solid rock made the feat of constructing a road across the Continental Divide quite the challenge.

Planning the GttSR

It wasn’t always certain that the GttSR would follow its current path.

Numerous proposals suggested various routes. One proposal drew the road from the southwest to the northeast, connecting Apgar to Many Glacier. Another had the road continuing on to Waterton Lakes in Canada.

Eventually, they settled on a route that would connect West Glacier with St Mary, closely following today’s path, but not exactly.

Surveys began in 1924 under Frank A. Kittredge of the Bureau of Public Roads. Each day, his crew would climb 3,000 ft (914 m) to walk along ledges and hang from ropes as they surveyed the route.

With such challenging work, Kittredge experienced a 300% labor turnover over the three-month survey project.

Inspecting the GttSR route

In 1924, Director of the National Park Service Stephen Mather and Glacier National Park

Superintendent Charles J. Kraebel were inspecting construction progress.

At one point, they were examining its steep approach to Logan Pass on the west side of the Continental Divide. National Park Service engineer George Goodwin’s initial proposal entailed 15 switchbacks as it ascended to Logan Pass, the highest point in the park (6,647 ft/2,026 m elevation).

National Park Service Landscape Architect Tom Vint opposed the route and lobbied to Mather an alternative route that involved only 1 switchback.

After several intense debates, Mather chose Vint’s plan, establishing the final route through the park with only one switchback (today, called “the Loop”), which the current Going-to-the-Sun Road follows.

Moreover, by the end of the ordeal, Mather had secured an agreement with the National Park Service and the Bureau of Public Roads for the construction of additional park roads throughout the west.

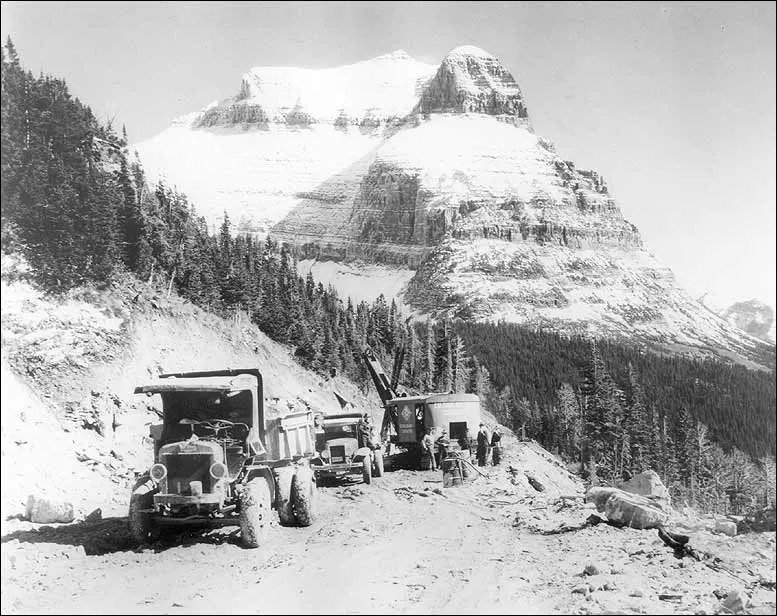

Constructing the GttSR

The construction of the GttSR was an engineering marvel for numerous reasons. Builders had to work within strict limitations to preserve the natural environment, minimize damage, and ensure the road blended in with its surroundings.

Only small explosives were allowed, as large explosives could do more damage to the surrounding area, and all bridges and support structures were to be constructed with materials excavated from the land and hillsides.

One of the most challenging sections to construct was the 405-foot (123-m) East Tunnel located east of Logan Pass. Because no power construction equipment could reach the site, all builders had to remove excavated rock from the site by hand.

By 1932, the Colonial Building Co. from Spokane, Washington, and A.R. Guthrie of

Portland, Oregon, completed the last remaining 10 miles of road east of Logan Pass, forever changing the way visitors experienced the park.

A journey through the park that used to take days on horseback could now be completed by car in a matter of hours.

Celebrating the finished road

After more than a decade of work, in the autumn of 1932, a car crossed the 51 miles of the Going-to-the-Sun Road for the first time. The road officially opened on July 15, 1933, with a celebration taking place on Logan Pass.

4,000 people gathered for a ceremony consisting of congratulatory speeches from Glacier National Park Superintendent Eivind Scoyen and chairman of the Montana State Highway Commission.

A chorus, a Star Spangled Banner performance from the Blackfeet Tribal Band, and a peace ceremony between the Flathead, Salish, and Kootenai tribes all took place.

While the road was completed in 1932, substandard sections of the road were later brought up to standard, with work beginning in 1938 to lay pavement over its crushed rock surface.

The Going-to-the-Sun Road was finally completed in 1952.

Going-to-the-Sun Road today

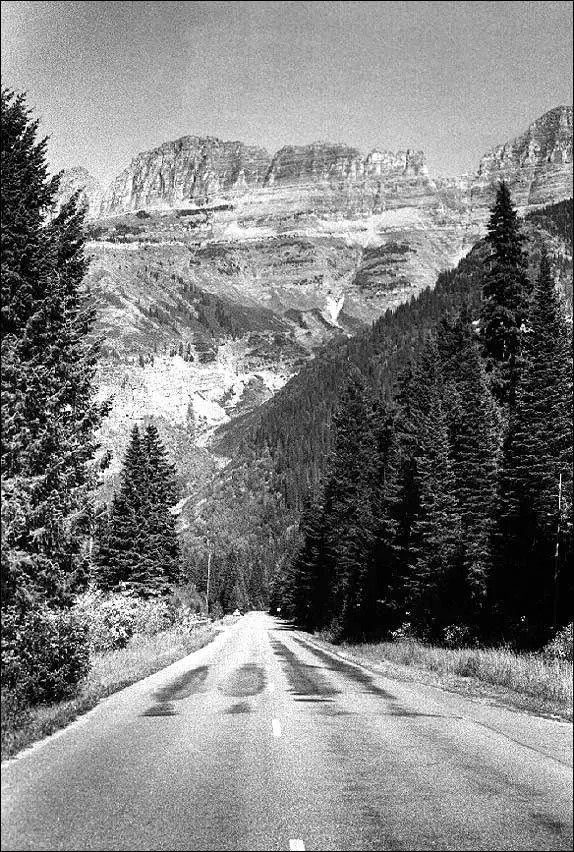

Today, the Going-to-the-Sun Road, also known as the Sun Road, stretches 50 miles west to east from West Glacier to St Mary. It takes two hours to drive from one end to the other, depending on traffic.

The Sun Road climbs up and over Logan Pass, the highest point in the park (6,647 ft/2,026 m), cutting across sheer mountain faces, past weeping walls of water, above deep valleys, and past free-falling waterfalls.

Visitors can stop at turnouts, viewpoints, and parking lots along the way to have a rest, learn about the park, take in the surrounding scenery, or set off on a trail into the wild areas of the park.

This engineering marvel is a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark and is on the list of the National Register of Historic Places.

Glacier National Park today

Today, Glacier National Park spans from northwestern Montana across the Canada-U.S. border where it becomes Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, Canada. Together, the two parks constitute the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park.

Glacier is managed by the National Park Service, which has its headquarters in the town of West Glacier. The National Park Service’s mission in Glacier is to implement park improvements, restore trails, and offer community programs, education, and youth programs centered around the park.

In an attempt to preserve the local ecology, activities that extract resources from the park, such as mining, logging, and hunting, are forbidden.

In addition to its breathtaking scenery, Glacier National Park is an officially designated Dark Sky Park, offering some of the best stargazing opportunities in Montana. A 20-inch (51-cm) observatory that is open to the public is located in St Mary.

The park has seen, on average, 2 million visitors annually since 2012.

Discover Montana’s National Parks

9 Breathtaking Montana National Parks + 6 Enchanting State Parks